Tales from the Yawning Portal. I’m not sure what to make of this product, but let’s start.

Tales from the Yawning Portal. I’m not sure what to make of this product, but let’s start.

The book is a collection of classic Dungeons & Dragons adventures updated for Fifth Edition, arranged so one could just go through each in order with a group of characters, campaign-like. None of the adventures link to any other. This is a book of nostalgia, bringing adventure modules from the early days of Dungeons & Dragons to “D&D Next” up to speed with current rules.

Aside from the nostalgia factor, I’m not certain why this book exists the way it does. Fifth Edition’s adventure offerings sold in stores have mainly been campaign-driven, from Tyranny of Dragons through Storm King’s Thunder. One-off adventures have been limited to the organized play program run at game stores. To me, it makes more sense to use a collection of those adventures to show 5e Dungeon Masters how to structure a 5e adventure.

Aside from the nostalgia factor, I’m not certain why this book exists the way it does. Fifth Edition’s adventure offerings sold in stores have mainly been campaign-driven, from Tyranny of Dragons through Storm King’s Thunder. One-off adventures have been limited to the organized play program run at game stores. To me, it makes more sense to use a collection of those adventures to show 5e Dungeon Masters how to structure a 5e adventure.

Take Tomb of Horrors, a classic adventure module. The design for this 1970s module doesn’t look like what design in the 2010s should be: the adventure is mainly linear and has a more adversarial DM versus player mindset than games in the past few decades have been. Despite this edition’s claim that Tomb of Horrors was supposed to be a “thinking person’s adventure”, TSR’s Lawrence Shick said the traps in the adventure were intended “not to challenge the intruders but to kill them dead.” (Wizards of the Coast from a few years back even wrote, “Gygax’s main purpose in creating Tomb of Horrors was to take his players down a peg.”)

The version I played, back when D&D was Advanced, involved several instances where you had to make saving throws or your character would die. Fifth Edition really goes out of its way to keep player characters from dying from a bad die roll or two, but in this update there are still plenty of insta-death: “…which is fatal, and all the characters in the … area are dead, with no saving throw, while any in the [nearby area] are slain unless they succeed on a DC 17 Constitution saving throw.” “Roll initiative. On initiative count 10, anyone still in [the area] is crushed against the roof and slain.”

But people love Tomb of Horrors. They want to play it. They’ve heard the stories. Can I survive the gauntlet, they wonder. Perhaps we all just make three or four level 18 heroes and see if we can get to the end. It’s part of D&D history, like Eric and the Gazebo or The Head of Vecna.

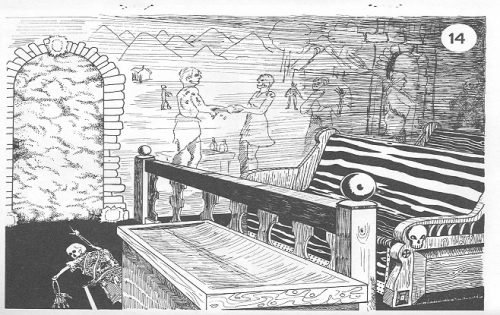

I feel that the form factor of the book hampers the re-envisioning of these classic adventures. The original version of Tomb of Horrors came with a twenty-page booklet of images for players to reference. When looking at a portal, for example, players could describe exactly what element they’re manipulating, or perhaps the illustration of an intricately detailed lock will give players a clue to solve the puzzle. Back when AD&D was around, there weren’t any skill checks — almost all of the solutions had to come from the players, not the characters.

These adventures (the older ones) also were originally published with a detached cover. The paper booklet would have the printed adventure, the cover (which could be used as a DM screen) had the maps for the adventure easy to access. As a hardcover book, the maps are printed in the pages of the book, leaving us with Dead in Thay’s massive Doomvault taking up all of page 111 with crazy tiny type and grid. (This map must have been printed as a poster-sized thing as we’re looking at a grid with about 25 divisions per inch.) However, I do like how they solve the solution for that adventure: closeups of the map appear in the adventure near relevant area descriptions. It’s a good way to keep access to the map near the important information.

Other adventures do this, like the Forge of Fury, but most are “here’s a map you’ll have to keep flipping back to” like the sprawling fortress level of The Sunless Citadel.

And while we’re at The Sunless Citadel, we’re going to loop back to 5e adventure design. This adventure was the first offering for D&D Third Edition. I’m not certain if people have the same nostalgic feeling for this (or Forge of Fury, the second in the line and in the book) as they did for Ravenloft, which begat Curse of Strahd, or this book’s Tomb of Horrors. But regardless, it seems to be a strange thing to include in this collection.

And while we’re at The Sunless Citadel, we’re going to loop back to 5e adventure design. This adventure was the first offering for D&D Third Edition. I’m not certain if people have the same nostalgic feeling for this (or Forge of Fury, the second in the line and in the book) as they did for Ravenloft, which begat Curse of Strahd, or this book’s Tomb of Horrors. But regardless, it seems to be a strange thing to include in this collection.

Take the first real area the adventurers access, the crumbled courtyard of the fortress. The floor of the courtyard is roughly twenty-five feet across to the entrance, but the floor is positively choked with rubble that slows movement. Why does it slow movement? No external threat exists: no time constraint to counter, no enemy able to spot the heroes the longer they stay out in the open. Just a series of DC 10 Acrobatics checks that stops movement if failed, or, if failed by five or more, prompts a 10% chance of a giant rat attack. “This encounter is why skill challenges were created,” writes a friend of mine. If you don’t fail any rolls badly enough, no rats to fight.

But that’s not all this area features. There’s a trap door that’s ten feet wide by ten feet long that drops people into a pit ten feet deep, which was triggered yesterday. Presumably, when the pit trap was triggered yesterday and the floor hinged downward, dumping the luckless goblin whose corpse is now below, all the rocks and debris and rubble also were dumped here. So when the heroes encounter this area, wouldn’t they see right in the center of this field of rubble a clear 10’x10′ square? Or are all the rocks magically glued to the pit trap cover, which is triggered by weight?

And the trap is only ten feet deep with the door hinged on one side, so all one really has to do is hop up when the door resets itself a minute later to climb out, assuming the door isn’t jammed into place with all of the rock that fell in, too.

Puzzled by the logic of this encounter — the first actual place in this adventure where things happen — I flipped ahead to a random room description in The Sunless Citadel, coming across a reference to make a DC 20 Wisdom (Perception) check. And then I glanced at the other area descriptions on the spread. They all call for Wisdom (Perception) checks. Flip to the previous page. “With a successful DC 15 Wisdom (Perception) check…” Flip forward. “With a successful DC 15 Wisdom (Perception) check…” “A successful DC 15 Wisdom (Perception) check made while searching…” Flip. “…separate DC 15 Wisdom (Perception) checks uncover…”

This is odd adventure design.

While there are some Strength checks, some Intelligence (Investigation) checks, and some Dexterity checks (and some Dexterity skill checks) in the adventure, it looks like the majority of things a character in Fifth Edition will do that’s not fighting is… perceiving. Just thumbing through the numbered encounter areas for the fortress level, there are twenty-one Wisdom (Perception) checks with the next most-numerous check to be made are either the seven basic Dexterity checks to unlock things with lockpicks or, if we’re looking at the skill list, the four Intelligence (Investigation) checks which are mostly made immediately after succeeding on a Perception check.

Again. Strange adventure design.

But there are elements baked into The Sunless Citadel for role-playing scenes, which is cool. It’s not all fights and Perception checks.

Forge of Fury is a better adventure (actually ranked #12 of D&D adventures of all time by gaming industry professionals in Dungeon magazine’s November 2004 issue). Christopher Perkins wrote, “To survive this adventure, the heroes must function as a team. The foes are smart and use their lairs creatively, and the black dragon at the end shows you don’t need a 20-foot wingspan to send adventurers screaming for their lives.”

The Hidden Shrine of Tamoachan is a mostly-linear trek through a Mayan/Aztec-flavored dungeon with a bit of an Indiana Jones-like trap-filled tomb feel. Like Tomb of Horrors, this originally came with a booklet of player handouts.

White Plume Mountain comes next (which I’ve always confused with Expedition to the Barrier Peaks), which is more of a less-lethal version of Tomb of Horrors. It’s a small dungeon with rooms that are crazy fun. Clark Peterson in that Dungeon magazine article says, “A battle against a giant crab in a dome at the floor of a volcanic lake? Check. Reverse gravity water tubes with kayaking bad guys? Check. A completely frictionless surface, studded with pit traps? Check.”

White Plume Mountain comes next (which I’ve always confused with Expedition to the Barrier Peaks), which is more of a less-lethal version of Tomb of Horrors. It’s a small dungeon with rooms that are crazy fun. Clark Peterson in that Dungeon magazine article says, “A battle against a giant crab in a dome at the floor of a volcanic lake? Check. Reverse gravity water tubes with kayaking bad guys? Check. A completely frictionless surface, studded with pit traps? Check.”

But then we get to Dead in Thay, which should be the closest thing to adventure design for Fifth Edition. This adventure was created for D&D Next, the playtest verison of what would eventually become the current edition of the game. It’s a gigantic adventure that’s a massive dungeon crawl, with the dungeon split up into different zones, presumably one zone for each week of the D&D Encounters organized play program. But like Tomb of Horrors, this was “a tribute to killer dungeons from the game’s history”.

So of the seven adventures published here, four are in the mold of the killer dungeon: Tomb of Horrors, Dead in Thay, The Hidden Shrine of Tamoachan, and White Plume Mountain.

The last we haven’t mentioned yet is Against the Giants, the bit of nostalgia that lies in wait to entrap me.

I remember running this back in the days of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons and loved it. It had direct ties into the drow series (Descent into the Depths of the Earth, Shrine of the Kuo-Toa, Vault of the Drow) and the Queen of the Demonweb Pits. Previously adapted for Fourth Edition, the maps have reverted back to approximations of the originals. (Fourth Edition needed large areas for combats due to the design of that system. Even the hallways and rooms of Hill, Frost, and Fire Giants weren’t nearly ludicrously large enough to handle combats in that edition!)

Rather than just have the adventure be the first of the three giants adventures, WotC counts all three of these as one large Against the Giants adventure. (The three adventures were repackaged as one huge module in the AD&D era.) The adventure’s start is nebulous here — I can’t recall if the originals had things happen before the heroes attack the steading of the hill giant chief or not — your heroes are “given the charge to punish the miscreant giants” being told that they can keep all the loot they find. Now, let’s ignore that the map of the timber fortress of the hill giants appears to be structurally unsound, or that the icy and rocky caves of the frost and fire giants just happen to end in a rectangular shape that fills a letter-sized piece of paper. I’m looking at this with fond memories. But in the back of my mind, I’m wondering about Storm King’s Thunder.

As we’ve covered last year, Storm King’s Thunder is more of a Fifth Edition riff on Against the Giants. While Storm King’s Thunder and this have interesting locales for the antagonists and interesting ways to deal with them, Against the Giants‘ setting seems more of a dungeon crawl; Storm King’s Thunder feels more like elements that would naturally occur in the fantasy setting of Dungeons & Dragons.

As we’ve covered last year, Storm King’s Thunder is more of a Fifth Edition riff on Against the Giants. While Storm King’s Thunder and this have interesting locales for the antagonists and interesting ways to deal with them, Against the Giants‘ setting seems more of a dungeon crawl; Storm King’s Thunder feels more like elements that would naturally occur in the fantasy setting of Dungeons & Dragons.

When I look back at Tales from the Yawning Portal, I realize I’m interested in Against the Giants because of that nostalgia feeling. I want to play this again. That’s exactly what this book is about. It’s not a good book for someone new to D&D, someone that has only experienced 5e. They would look at these adventures and walk away, confused. It’s not for them.

It’s a book for the older players.

It’s a book for the ones that came in during Third Edition with The Sunless Citadel and The Forge of Fury. The ones from the days of Advanced D&D with Against the Giants and Tomb of Horrors. The ones from the early days of D&D with White Plume Mountain and The Hidden Shrine of Tamoachan.

It’s not a good book for someone looking to run 5e games. But it is a good book for seeing how the games you played in your early days of roleplaying would work with the contemporary ruleset.

So what is this book?

The book is a collection of classic Dungeons & Dragons adventures updated for Fifth Edition, arranged so one could relive adventures from one’s gaming youth; a book of nostalgia, bringing adventure modules from earlier editions of Dungeons & Dragons into the current ruleset. And that’s good enough for me.

Addendum: I just received a copy of Curse of Strahd, which has a map of the area (and several locations) bundled in the back like a fold-out poster. I don’t see why they didn’t do something similar here, with perhaps the player’s map of the Doomvault on one side and the other side, in each folded section, maps for the DM for the different adventures. It would make referencing the adventure locations so much easier. For that matter, why not a pdf map packet for download at Wizards.com?

Tales from the Yawning Portal is available today at major book retailers for $49.95. You can also find online gaming versions of Tales from the Yawning Portal at Fantasy Grounds, Steam, and Roll20.

A copy of Tales from the Yawning Portal was provided by Wizards of the Coast free for review.

In the comments! What classic D&D adventures would you have chosen for an update to Fifth Edition?

When I reviewed Princes of the Apocalypse, I commented that the first half of the book “can almost be used as just a setting book for the Dessarin Valley”. But that didn’t prepare me for what I’d find when opening up Storm King’s Thunder: over a fifth of this 256-page book is devoted to quick looks at an area that makes up the Dessarin Valley, and areas north of Mirabar, south past Daggerford, and as far east as Anauroch. Those “quick looks” are anywhere from a paragraph of few lines to a full page, several with suggested encounters (most centered around the giant activities that drive this book’s campaign). In the section before that, two major locations in the Dessarin Valley are detailed (and one location far to the north). Combine this with Princes of the Apocalypse, and you’ve got a fantastic gazetteer for your campaign. A section of Mike Schley’s Forgotten Realms map is used in that 50+ page setting section.

When I reviewed Princes of the Apocalypse, I commented that the first half of the book “can almost be used as just a setting book for the Dessarin Valley”. But that didn’t prepare me for what I’d find when opening up Storm King’s Thunder: over a fifth of this 256-page book is devoted to quick looks at an area that makes up the Dessarin Valley, and areas north of Mirabar, south past Daggerford, and as far east as Anauroch. Those “quick looks” are anywhere from a paragraph of few lines to a full page, several with suggested encounters (most centered around the giant activities that drive this book’s campaign). In the section before that, two major locations in the Dessarin Valley are detailed (and one location far to the north). Combine this with Princes of the Apocalypse, and you’ve got a fantastic gazetteer for your campaign. A section of Mike Schley’s Forgotten Realms map is used in that 50+ page setting section.

Your players will be at one of the three locations very early in the campaign, defending the location from attack. However, you’re not just playing your heroes, each player at the table is given an NPC they’re in control of. While the battle rages on, your heroes and these others aren’t necessarily in the same location. The NPC survives? They’ve got some storylines your players can follow up on, things that require your heroes to travel quite some distance to complete – one has your heroes escorting the character to the next town over to meet their boss who then tasks them to safeguard a wagon to a town way the heck far away after which they get an anonymous bundle that directs them to a town even further away in the opposite direction where they’ll get their final reward which is pretty cool indeed.

Storm King’s Thunder seems to have a lot of travelling involved.

It feels natural to compare Storm King’s Thunder to Princes of the Apocalypse. Both take place in the same general area (although this giant adventure can take heroes far afield from the valley). Both have a preferred story progression while including some free-form events. Both have a large section dedicated to the overall setting, tempting the Dungeon Master to make it her own. However, while Princes is set up assuming the heroes would tackle the elemental cults and temples in a level-appropriate manner, there’s nothing stopping a group of 4th level heroes from stumbling into an area designed for 7th level adventurers, complete with a staircase leading down to a place for 10th level heroes, Storm King’s Thunder has an adventure flowchart designed to avoid just that issue. This isn’t to say there’s a lack of choices for the players.

The adventure proper begins with a choice of the three locations mentioned earlier. If your heroes head to the major location far to the north, they don’t have the adventuring goodness that’s at the two different major locations in the Dessarin Valley. Likewise, the middle part of the campaign offers to take the heroes to multiple locations, but they only need to go to one to progress to the conclusion. This final act has some branching options as well. In other words, my group playing Storm King’s Thunder will most likely have a wildly different story to tell than your group playing the same campaign.

The adventure proper begins with a choice of the three locations mentioned earlier. If your heroes head to the major location far to the north, they don’t have the adventuring goodness that’s at the two different major locations in the Dessarin Valley. Likewise, the middle part of the campaign offers to take the heroes to multiple locations, but they only need to go to one to progress to the conclusion. This final act has some branching options as well. In other words, my group playing Storm King’s Thunder will most likely have a wildly different story to tell than your group playing the same campaign.

Storm King’s Thunder forgoes standard XP and leveling, opting to reward the players by completing goals. Each section of the book has a character advancement sidebar, giving direction for when the heroes gain levels. Thus, that middle part of the campaign where the players have multiple paths but only need one to advance the storyline, they all hit 9th level when completing that mission. Less bookkeeping, more adventure, if you ask me.

The cartography is all over the place within this product. However, unlike earlier storyline campaign books, none of the maps are signed, so it’s difficult to tell who did what. You’ve got some things that look more like general fantasy maps instead of something worthy of the word “cartography”. You’ve got small maps that incorporate hand-drawn imagery to stuff that looks like it’s built using basic shapes in Illustrator or thrown together using different terrain packages in Roll20. Then you’ve got the map of Triboar, which looks completely hand-drawn. There are six different cartographers listed in the credits, all with differing styles. This probably won’t bother you, but in my day job as a graphic artist working with book layouts similar to this, it bugs the heck out of me.

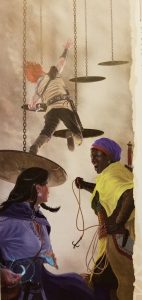

The artwork, also with some varying styles, is much more in sync. Those NPCs your heroes could control? There’s eighteen of them with a large range of body sizes, skin color, and ethnicity (if you translate all the fantasy races over to “human”). The collage of images on the cover is impressive – you can see the standalone King Hekaton on the first page of the book and the combined illustration collage before graphic elements were added to it on the second page.

Several tie-ins to this storyline are available and planned, including an Assault of the Giants boardgame from WizKids, Roll20 and Fantasy Grounds ready-made adventures, and more.

A copy of Storm King’s Thunder was provided free for review by Wizards of the Coast.

- Comments Off on Second Look – Storm King’s Thunder

Storm King’s Thunder

10 Sep

Posted by David Miller as Electronic Games, Miniatures, Modern Board Games, RPGs, War Games

The latest story-line for Dungeons & Dragons saw its official launch this week with the full retail release of the Storm King’s Thunder adventure book ($50 suggested retail). Developed in-house at Wizards of the Coast, Storm King’s Thunder sees the player characters defending the Sword Coast in The Forgotten Realms against the depredations of ravaging giants.

The latest story-line for Dungeons & Dragons saw its official launch this week with the full retail release of the Storm King’s Thunder adventure book ($50 suggested retail). Developed in-house at Wizards of the Coast, Storm King’s Thunder sees the player characters defending the Sword Coast in The Forgotten Realms against the depredations of ravaging giants.

The adventure covers character levels 1-11, for the first five in a more traditional progression and in the later levels with a modular approach. The book includes an adventure flowchart to help guide the dungeon master, as well as an appendix with suggestions for integrating it with other published adventures. Part of the story involves the characters making use of the giants’ own rune magic to craft new fantastic items.

For those playing Dungeons & Dragons remotely online, licensed versions of Storm King’s Thunder are also available in Fantasy Grounds ($35) and Roll20 ($50). The story line makes an appearance as an expansion to the Neverwinter MMO. And coming from WizKids are a Storm King’s Thunder Icons of the Realms miniatures series (later this month) and an Assault of the Giants board game ($100, May 2017).

- Comments Off on Storm King’s Thunder

Trending

- Massdrop.com

- Oh the Irony—Illuminati Card Game Continues to Inspire Conspiracy Theorists

- Home

- Footprints, an Educational Ecology Game

- USPS Adds Board Game Flat Rate Box

- Baila, the Estonian Drinking Card Game

- Crystal Caste Wins Dice Patent Suit Against Hasbro

- Mirror Game, Red and Blue

- Are Board Games Dangerous?

- The Truth About Dominoes On Sunday in Alabama

Archives

Most Popular Articles

- Oh the Irony—Illuminati Card Game Continues to Inspire Conspiracy Theorists

- The 20 Most Valuable Vintage Board Games

- The Truth About Dominoes On Sunday in Alabama

- Sequence Game, and Variants

- USPS Adds Board Game Flat Rate Box

- Baila, the Estonian Drinking Card Game

- The 13 Most Popular Dice Games

- Are Board Games Dangerous?

- Guess Who? The Naked Version

- What Happened to the Jewel Royale Chess Set?

Recent Posts

- Toy Fair 2019—Breaking Games

- Talisman Kingdom Hearts Edition

- Toy Fair 2019—Winning Moves

- Toy Fair 2019—Games Workshop

- Toy Fair 2019—Star Wars Lightsaber Academy

- Toy Fair 2019—Stranger Things Games

- Toy Fair 2019—HABA

- Licensing Roundup

- Game Bandit

- 2018 A Difficult Year For Hasbro But Not For D&D Or MtG

Recent Comments

- on Toy Fair 2019—Winning Moves

- on Game Bandit

- on Second Look—Dungeons & Dragons Waterdeep Dragon Heist

- on Crowdfunding Highlights

- on Beyblade SlingShock

- on Game Bandit

- on Game Bandit

- on Watch This Game!, the Board Game Review Board Game

- on Second Look—Vampire: The Masquerade 5th Edition

- on Palladium Books Loses Robotech IP License, Cancels Five-Year-Overdue Robotech RPG Tactics Kickstarter